In The Wake of Lewis and Clark

FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE SEA

Synopsis

Thomas Jefferson, president of the young United States of America, was an optimist who also had a shrewd understanding of geopolitics. His young country was blocked from expanding to the north by Great Britain, to the south and west by Spain, and, after 1800, by France. The immense Louisiana Territory effectively blocked his vision of an America that would someday extend from sea to shining sea. Even before he learned, in 1803, that he would be able to buy Louisiana from France, be began his plans to explore what he knew must someday become American territory.

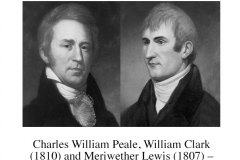

The daring enterprise was so important that he assigned its leadership to Meriwether Lewis, his own personal secretary. Lewis, in turn, recruited his former commanding officer, William Clark, to co-captain the expedition.

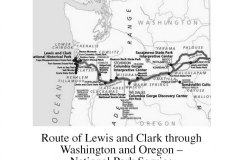

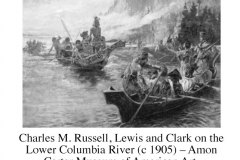

Leaving St. Louis on May 14, 1804, with thirty-four soldiers, hired voyagers, and Clark’s slave, York, they traveled through the unexplored territory and beyond it, to the Pacific Ocean. Their exploits come alive today as cruise ships travel their route up and down the Snake and Columbia Rivers.

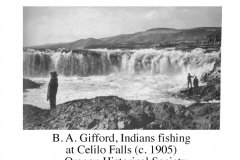

This book is designed to help passengers better understand what the Lewis and Clark expedition experienced during those momentous years of 1804–1806, but also to be able to see through vintage photographs and other images what the members of the Corps of Discovery saw before the rivers were changed forever by hydroelectric dams. It affords an opportunity to travel “in the wake of Lewis and Clark.”

Fact Sheet

Excerpt

Reviews

Gallery

Fact Sheet

Fact Sheet

| Title | IN THE WAKE OF LEWIS & CLARK: From the Mountains to the Sea |

| Author | C. Mark Smith |

| Publication Date | March, 2015 |

| Marketing Plan | Onboard Sales, Online Sales, Internet, Libraries |

| Audiences/Markets | Lewis & Clark Expedition (1804-1806), Biography; (to be expanded) |

| Binding | 6 x 9 Perfect Bound |

| Features | 10 Chapters, 22 Pictures, Biography |

| Pages | 95 |

| ISBN: | 978-1-4834-2839-0 (sc)978-1-4834-2838-3 (e) |

| Publisher: | LuLu Publishing Services |

| Price: | $14.95 |

| Copyright: | 2015 © Shore Excursions of America |

| Website: | www.cms-author.com |

| Author Contact: | smithcmark@gmail.com |

Excerpt

The Seven Years’ War—known as the French and Indian War to Americans—was the first truly global conflict. It was fought between 1756–1763 on the battlefields of Europe, in the backwoods of North America, on islands in the Caribbean, in Central America, along the West African coast, in India, and in the Philippines.

The war was just the latest in a series of wars between the European empires during the eighteenth century that was driven by the struggle for power and influence in Europe and the growing competition for trade and new colonies in the rest of the world. Prussia and her allies were in competition with Austria for control of what remained of the Holy Roman Empire. Great Britain competed with France and Spain for new overseas territories, untapped resources, and strategic control of key choke points around the world’s oceans.

Power and influence ebbed and flowed as Europe’s great monarchies sought a new balance of power. Newly emerging Prussia formed an alliance with Great Britain. They were joined by several smaller German states and later, Portugal. In North America, the great Iroquois Confederacy fought on behalf of the British, while the Huron and other tribes allied with the French. Traditional enemies France and Austria countered with their own alliance, which was joined by Sweden, Saxony, and later, Spain. Russia started out as Austria’s ally but later signed a separate peace with Prussia. In India, the Mughal Empire allied with the French.

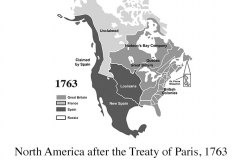

North America after the Treaty of Paris, 1763

The results of the Seven Years’ War generally favored the British, who gained most of New France in Canada as a result of General James Wolfe’s 1759 defeat of the French army under Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham above Quebec City. Britain also gained Spanish Florida, several islands in the Caribbean, and the colony of Senegal on the West African coast, and forced the French out of India. Spain lost Florida but gained the vast French holdings in Louisiana while regaining Cuba and the Philippines, which had been captured by the British during the war. The cost of undertaking a war on such a vast scale nearly bankrupted the different antagonists.

In North America, none of the great powers had any real knowledge of the vast Louisiana Territory. For centuries, great powers’ sea captains had searched both coasts of the continent looking for a “Northwest Passage” to the Orient. Over time the search had extended to North America. The seventeenth-century French explorers Marquette, Hennepin, and LaSalle suggested that there was a single mountain chain somewhere in the western interior beyond which a great river flowed into the Pacific Ocean.

Britain’s North American colonies fought alongside the mother country, particularly against the French-backed Indian tribes in the north and west. However, after the expense of protecting their colonies, the British government felt that their increasingly prosperous colonies should pay for their own defense. They made the decision to recover some of their costs by imposing a series of taxes, including one that taxed every document or newspaper used or printed in America. The colonists were outraged that they were being taxed without representation in Parliament, a violation, they felt, of their rights and liberties. The taxes were met by acts of civil disobedience and growing calls for independence. By 1767, events had escalated to the point where Britain imposed a tax on all goods imported into their American colonies, and the colonists responded by boycotting British imports and halving their trade with England. Not surprisingly, King George III and his government regarded the colonists’ actions as insurrection and sent troops to Boston to restore the status quo.

The British government seriously underestimated the power of the American independence movement, particularly among the colonies’ leading political and intellectual leaders. The charged atmosphere could not last, and by 1774, England and her American colonies were at war. The Americans formally declared their independence two years later. In spite of hired German mercenaries and the largest overseas deployment by their naval and land forces in history, the British were never able to apply enough military force or political willpower to win the war. They could defeat the Americans in battle, but they couldn’t control the countryside that sustained and nurtured their foe.

North America after the Treaty of Paris, 1783

By 1778, the French saw an opportunity to strike back at the British for their losses during the Seven Years’ War and signed an alliance with the new government of the United States. The arrival of French land and naval forces added a new dimension to the war, making it more difficult for the British to reinforce their forces and providing the pivotal margin of victory in the decisive Battle of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. Within six months, the British prime minister resigned, and a peace treaty was signed in Paris in September 1783.

Financial crises at home and the success of the Americans in creating their republic only increased the ambitions of those who wanted to reform the government of France. The state of the country’s finances and Louis XVI’s inconclusive and high-handed attempts to deal with the radical reformers led to the overthrow of the French monarchy in 1789. The events in France led Europe’s other conservative monarchies—primarily Austria and Prussia—to form a coalition aimed at restoring the French monarchy. Revolutionary France then declared war on Austria and Prussia in 1792, and on England in 1793. France and England would be at war continuously until 1802.

The young United States of America tried to stay out of the European conflict while profiting by trading with both sides. Both France and England tried to prohibit America from trading with the other side. With no real navy to protect them, American merchant ships were routinely stopped and searched, particularly by England, and their seamen—many of whom had been born in Great Britain—were removed and impressed to fill the ranks of the Royal Navy.

Spain had claimed the Pacific Coast of California as early as 1542, but other priorities in the New World meant that California would remain an imperial backwater until 1765 when Spain learned that Russians were settling in northern California. By then, Spain was fully engaged in the Seven Years’ War but decided to colonize the province of Alta California with Franciscan monks protected by troops stationed at their missions.

Spanish claims to Alaska and the west coast of North America dated back to the papal bull of 1493, which created the demarcation line between Spain and Portugal in the New World. Spain’s claim was reinforced in 1513 when Vasco Núñez de Balboa claimed all lands adjoining the Pacific Ocean for Spain.

In 1579, the British adventurer Francis Drake sailed up the west coast of North America, perhaps as far as British Columbia, before returning south to repair his ship in what is now San Francisco Bay. There, he claimed the region for England, naming it New Albion. Around 1592, a Greek explorer employed by Spain, Juan de Fuca, was supposed to have discovered the strait of water, now named for him, separating Vancouver Island from the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State. In the 1740s, the Danish explorer Vitus Bering—then in the employ of Elizabeth, Empress of Russia and daughter of Peter the Great—explored Alaska and the Pacific Coast, leading to Russia’s claim to that region and the eventual settlements in northern California that would so alarm the Spanish.

Beginning at about the same time as the American Revolution, Spain actively explored the coastline of what is now Canada and Alaska in order to counter the Russian and British threats there and strengthen their own claim. They discovered the vast quantities of fine fur pelts that were available for trade from the local Indian tribes. On August 17, 1775, a Spanish sea captain named Bruno de Heceta sighted the mouth of the Columbia River but could not tell if it was a river or a strait between several bodies of land. Unable to enter because of the strong currents, he named it Bahia de la Asunción.

Over the next ten years the Spanish accelerated their exploration of the region and established a trading post at Nootka Sound. They soon controlled the fur trade between Asia and North America. In 1778, Captain James Cook of the British Royal Navy visited Nootka Sound, and it was not long before the British and Americans were intent on competing with the Spanish for the increasingly profitable trade.

In 1788, an American trader, Captain Robert Gray of Boston, discovered a large river at approximately 46° latitude but was unable to enter it because of the adverse tides and currents. He proceeded north to Nootka Sound, where he was joined by a second American as well as several British trading ships. The Spanish Navy had dispatched a warship to Nootka to enforce Spanish sovereignty and impounded the three British ships it found there. The two American ships were left alone because Spain had been allied with France and the United States during the recent American Revolution. When news of the capture of the British ships arrived back in England, it almost led to war between Britain and Spain. The Nootka Convention of 1790 allowed both countries the right to settle along the Pacific Coast, interrupting Spain’s expansion in the New World for the first time in more than two centuries.

In May 1792, Robert Gray was finally successful in sailing into the Columbia River in his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, becoming the first recorded non-Native-American to do so. That voyage became the basis for the United States’ claim on the Pacific Northwest, and the river was afterwards named for Gray’s ship. Later that same year, Royal Navy Lieutenant William Broughton, in the service of Captain George Vancouver, entered the Columbia in his ship, Chatham, and rowed up the river in the ship’s boats as far as the current-day town of Washougal on the Washington side. His charts eventually found their way into an American map prepared for the Lewis and Clark expedition. It is quite possible—even probable—that Jefferson did not believe that Gray’s discovery of the Columbia established a clear claim to the region on behalf of the United States and that the Lewis and Clark expedition was expressly designed to strengthen that claim.

While England, Spain, and the United States competed for the Pacific Northwest and the fur trade with China, momentous events were taking place back in the heartland of the North American continent. France had controlled this vast area—which included the entire drainage system of the Mississippi River, from the Appalachian to the Rocky Mountains—from 1699 until 1762. As negotiations to end the Seven Years’ War began, Louis XV of France secretly proposed to his cousin, Charles III of Spain, that France give Louisiana to Spain. The agreement was kept secret even during the negotiation and signing of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Seven Years’ War in 1763. The Treaty of Paris divided La Louisiane—as the vast territory was known in French—in half, with the Mississippi River as the dividing line. As a result of England’s victory in the Seven Years’ War, the half east of the Mississippi was given to England, while the western half, including New Orleans, was nominally retained by France, which had already secretly promised it to Spain.

Spain would only control its remote and unruly territory for thirty-six years. By 1800, Napoleon Bonaparte had become First Consul of France. He dreamt of establishing a new French empire in the Caribbean and Louisiana. In another secret treaty, in which he gave the King of Spain’s son-in-law control over the province of Tuscany in Italy, Spain agreed to return Louisiana to France.

Thomas Jefferson, who had once served as Minister to France and Secretary of State before being elected as the third President of the United States, was a renaissance man who spoke five languages, understood geopolitics, and had a strategic vision of the future of the United States. In the spring of 1801, Jefferson learned of the secret treaty between Spain and France. Alarmed, he let the French know that the United States would consider any stationing of French troops in Louisiana to be an act of war.

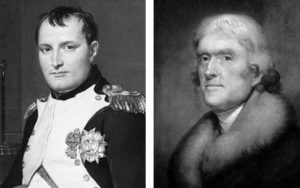

Left: Jacque-Lewis David, the Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (1812) – National Gallery of Art. Right: Rembrandt Peale, Thomas Jefferson (1805) – New York Historical Society.

In Jefferson’s mind, so long as Louisiana remained a part of the dying Spanish empire, the United States could bide her time. The control of Louisiana by the active and aggressive Napoleon was another matter entirely. Control of the territory by the British represented the greatest threat of all.

In May 1793, a Scottish fur trader named Alexander Mackenzie, working for the British North West Company, set out from Montreal for the Pacific Ocean with a small party. He crossed the Continental Divide and reached the headwaters of the Frazier River, but when told that it was unnavigable and occupied by hostile Indians, he selected another route to the coast. Mackenzie’s exploration was of immense importance to the Americans. He believed that he had discovered the northern fork of what would come to be called the Columbia River, and the publication of his journal established the British claim to the region.

Jefferson had long been interested in the west. He knew the approximate location of the mouth of the Columbia River from Gray’s discovery. When Mackenzie’s journal was published in London in 1801, Jefferson quickly acquired a copy of it. Mackenzie wrote that “the way to the Pacific lay open and easy,” and it prompted Jefferson to take action.

He sent Robert R. Livingston to Paris to inquire about purchasing New Orleans and its immediate environs from France. Negotiations languished while Napoleon’s armies were forced from Egypt and tried unsuccessfully to put down a slave revolt in Haiti. Desperate to avoid a possible war with France, Jefferson sent James Monroe to Paris in 1802 to help Livingston negotiate a settlement, with instructions to negotiate an alliance with England if the talks in Paris failed.

Louisiana Purchase, 1803

Jefferson had authorized Livingston to purchase New Orleans and its immediate environs at a cost not to exceed $10 million. At first Napoleon was uninterested, but his recent losses and the need to rearm in order to continue the war with England forced him to reconsider. The American negotiators were shocked when the French offered them New Orleans and all of the Louisiana Territory for only $15 million. The American negotiators accepted the French offer—hoping that Jefferson and the American congress would concur—on April 30, 1803. The treaty was quickly signed by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in October 1803.

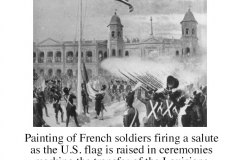

France officially turned over the Louisiana Territory to the United States at a formal ceremony conducted in St. Louis on March 10, 1804. The Louisiana Purchase roughly doubled the physical size of the United States, adding 828,000 square miles at a cost of $11,250,000 in cash plus the assumption of an additional $3,750,000 of private American debt—approximately four cents per acre.

Reviews

Amazon

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Four Stars. Well written with current info overlaid with Lewis and Clark expedition.

Four Stars. Well written with current info overlaid with Lewis and Clark expedition.

dchris

April 10, 2016

Goodreads

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Four stars! I really liked it.

Four stars! I really liked it.

Margaret M. Myer

August 24, 2016